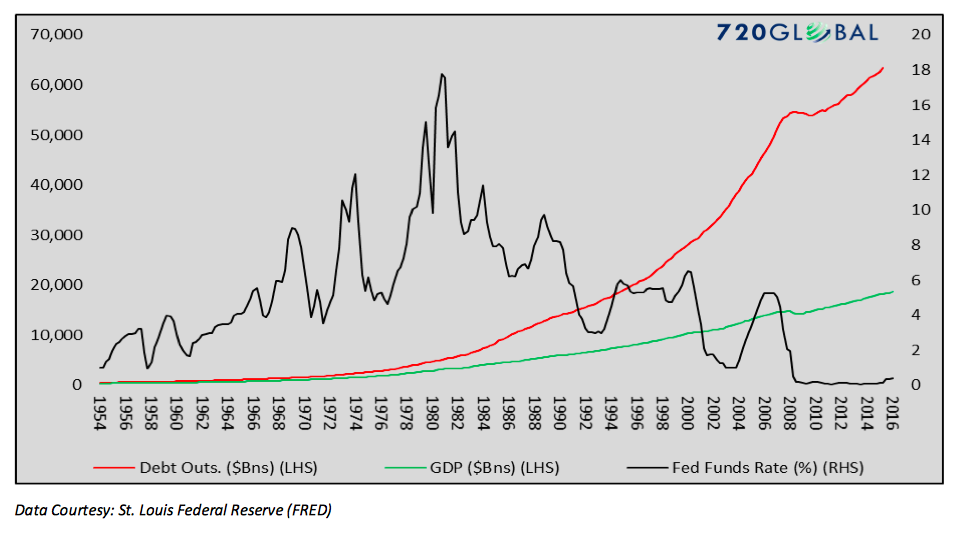

Since 1982, the duration (price risk) of nominal U.S. Treasury securities has risen 70% while the average coupon, or margin of safety, has dropped 85%. Meanwhile, the total amount of U.S. public federal debt has exploded higher by 1,600% and total U.S. credit market debt, as last reported by the Federal Reserve in 2015, has increased over 1,000% standing at $63.4 trillion.

When contrasted with nominal GDP ($18.6 trillion) as graphed below, one begins to gain a sense for how radically out of balance the accumulation of debt has been relative to the size of the economy required to support and service that debt. In other words, were it not for the steady long-term decline in interest rates, this arrangement likely would have collapsed under its own weight long ago.

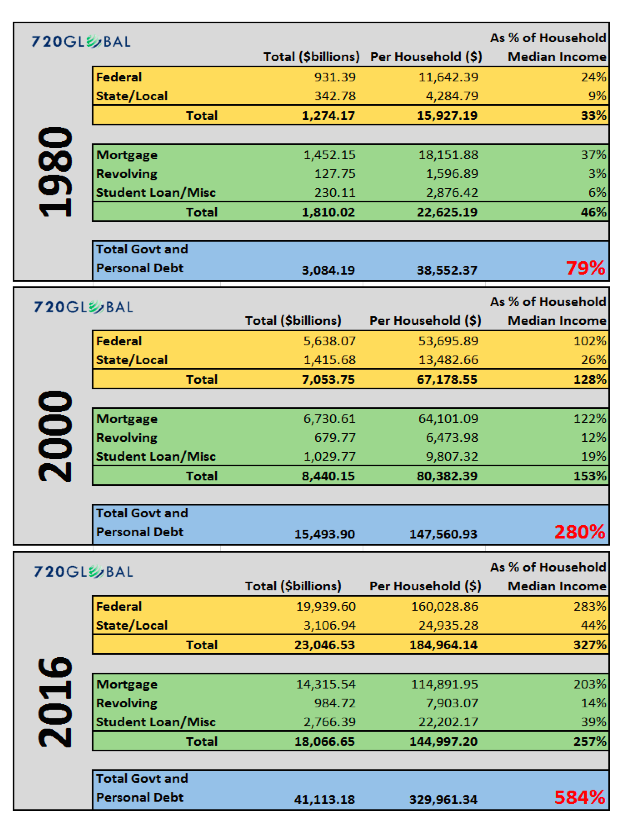

To provide a slightly different perspective, consider the three tables below, which highlight the magnitude of government and personal debt burdens on an absolute basis as well as per household and as a percentage of median household income.

Data Courtesy St. Louis Federal Reserve (FRED) and USdebtclock.org

If every U.S. household allocated 100% of their income to paying off the nation’s total personal and governmental debt burden, it would take approximately six years to accomplish the feat (this calculation uses aggregated median household incomes). Keep in mind, this assumes no expenditures on income taxes, rent, mortgages, food, or other necessities. Equally concerning, the trajectory of the growth rate of this debt is parabolic.

As the tables above reflect, for over a generation, households, and the U.S. government have become increasingly dependent upon falling interest rates to fuel consumption, refinance existing debt and pay for expanded social and military obligations. The muscle memory of a growing addiction to debt is powerful, and it has created a false reality that it can go on indefinitely. Although no rational individual, CEO or policy-maker would admit to such a false reality, their behavior argues otherwise.

Investors Take Note

This article was written largely for investors who own securities with embedded interest rate risks such as those described above. Although we use U.S. Treasury Notes to illustrate, duration is a component of all bonds. The heightened sensitivities of price changes coupled with historically low offsetting coupons, in almost all cases, leaves investors in a more precarious position today than at any other time in U.S. history. In other words, investors, whether knowingly or unknowingly, have been encouraged by Fed policies to take these and other risks and are now subject to larger losses than at any time in the past.

This situation was beautifully illustrated by BlackRock’s CIO Rick Rieder in a presentation he gave this fall. In it he compared the asset allocation required for a portfolio to achieve a 7.50% target return in the years 1995, 2005 and 2015. He further contrasts those specific asset allocations against the volatility (risk) that had to be incurred given that allocation in each respective year. His takeaway was that investors must take on four times the risk today to achieve a return similar to that of 1995.

Summary

We generally agree with Stanley Druckenmiller. If enacted correctly, there are economic benefits to deregulation, tax reform and fiscal stimulus policies. However, we struggle to understand how higher interest rates for an economy so dependent upon ever-increasing amounts of leverage is not a major impediment to growth under any scenario. Also, consider that we have not mentioned additional structural forces such as demographics and stagnating productivity that will provide an increasingly brisk headwind to economic growth. Basing an investment thesis on campaign rhetoric without consideration for these structural obstacles is fraught with risk.

The size of the debt overhang and dependency of economic growth on low interest rates means that policy will not work going forward as it has in the past. Although it has been revealed to otherwise intelligent human beings on many historical occasions, we retain a false belief that the future will be like the past. If the Great Recession and post-financial crisis era taught us nothing else, it should be that the cost of too much debt is far higher than we believe. More debt and less discipline is not the solution to a pre-existing condition characterized by the same. The price tag for failing to acknowledge and address that reality rises exponentially over time.

Thanks for reading.

Note that my firm will soon be offering “The Unseen”, a subscription-based publication similar to what has been offered at no cost over the past year and a half. Stay tuned.

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.