Many financial assets, especially those that are the riskiest, are priced well above their respective fundamental values.

A thank you primarily belongs to unprecedented monetary policy conducted on a domestic and global scale by central bankers. The vast financial rewards and temporary economic stability attributed to central bank actions appear to be blinding many investors to the longer-term consequences of these actions and the implications for their investments in an era of monetary policy normalization.

Accordingly, we discuss the proverbial fly in the ointment, or what might prevent central bankers from being able to successfully “manage” markets with their extraordinary policies.

The Fed Put

Many investors assume that, if the equity markets decline in a meaningful way, the Federal Reserve (Fed) will once again spring into action to halt the decline. The so-called “Fed Put” is not new; in fact, it was originally coined the “Greenspan Put” due to the actions of Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan following the 1987 stock market crash.

At that time, the Fed led by Greenspan added liquidity to the financial system to comfort investors and make them willing to buy financial assets. Ever since the Fed has been increasingly active vocally and via monetary policy in attempting to stem sharp market declines.

It is important to understand that the Fed does not stop stock market declines by purchasing stocks directly. They provide verbal influence and liquidity to banks which works its way through the financial plumbing to the markets.

Therefore, and of huge importance, the effectiveness of Federal Reserve actions is highly dependent on the trust and willingness of investors.

To retain this trust, the Fed must remain vigilant of market conditions.

The Federal Reserve’s attentiveness has been on full display since the Financial Crisis of 2008. On numerous occasions since the Crisis, relatively minor equity index declines elicited speeches by Fed members to subtly, and not so subtly, remind the market of their money printing capabilities. In fact, even when markets rested at all-time highs, they have been quick to remind the public of their abilities. The following two examples serve as evidence:

- On the morning of October 15, 2014, with the S&P 500 down over 3% on the day and nearly 10% since mid-September, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President and FOMC voting member James Bullard stated that QE might be extended. This was curious, to say the least, considering that in the weeks prior he mentioned that it was time to reduce QE. Bullard’s simple reminder of QE spurred the bulls to actions. From the moment he mentioned QE, the S&P 500 rallied over 2% and closed the day down less than 1%. In the two weeks following, it rose another 10% and closed the month at record highs. That action was later deemed the “Bullard Stick Save.”

- We were recently reminded of this in the fourth quarter of 2018. By Christmas Eve stock markets were down nearly 20% over the preceding three months. Within a month, Jerome Powell and the Fed all but put an end to further rate hikes and halted quantitative tightening (QT). These actions were ultimately made official in the months following and all with negligible economic evidence to support such a sharp reversal in monetary policy.

Inflation and the U.S. Dollar

Over the last 30 years, the Fed’s primary weapon to support markets has been interest rate reductions using the Fed Funds target rate. Since 2008, money printing, technically known as quantitative easing (QE), was introduced as the zero bound on interest rates constrained the Fed from reducing the Fed Funds rate further. Lower interest rates and QE have proven to be an incredibly powerful driver of asset prices, but only as long as inflation is benign and the dollar is relatively stable.

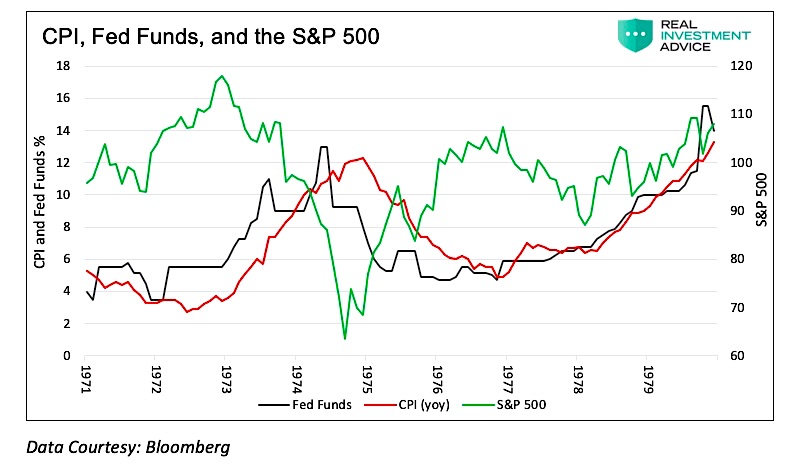

Inflation: Before the low and stable inflation environment of the last 20 years, inflation was much more of a concern. From 1972 to 1980, inflation, as measured by annual changes in the consumer price index (CPI), increased from 3% to nearly 15%. Under Chairman Paul Volcker (1978-1987) and Arthur Burns (1970-1978), the Fed aggressively increased the Fed Funds rate to put a lid on inflation and reinforce confidence in the U.S. dollar. These leaders prescribed the necessary medicine with little regard for the stock market.

The graph above compares Fed Funds and CPI to the S&P 500 in the 1970s. Note that, in 1973 and 1974 under the chairmanship of Arthur Burns, the Fed aggressively removed liquidity from the financial system by raising the Fed Funds rate despite mounting losses in the S&P 500.

Had the Fed sat on their hands out of concern for stock prices, it is quite likely inflation would have kept rising and the dollar may have been at risk of losing its status as the world’s reserve currency. That would have produced global turmoil along with massive repercussions for economic growth for years to come. The Fed prescribed medicine that would further aggravate current economic woes but with the promise of a healthier domestic and global economic environment in the future.

Currently, inflation hovers near the Fed’s target level and they characterize risks to growth as balanced. However, asset inflation resulting from the Fed’s easy money policies is soaring. Stock prices, as measured by prices and importantly valuations, and at or near record highs, largely due to excessive amounts of liquidity injected by global central banks to combat the financial crisis. Interest rates remain at historically low levels and credit spreads near some of the tightest levels of the last 50 years.

Art, classic cars, high-end real-estate, and a host of other assets are engulfed in the same mania driving more traditional financial assets.

Recently we have seen some data from corporate earnings reports and corporate surveys that suggests inflation is starting to form. Although still weak, wages have also turned higher. Price pressures are still benign, but if inflation were to suddenly rise beyond the Fed’s 2% target, the Fed would become more vigilant.

While the Fed believes some inflation is a sign of a healthy economy, they do not want rampant inflation and the associated economic consternation resulting from significantly higher interest rates. Given the enormous debt burden of the U.S. government, corporations, and households, the impact of higher inflation and higher interest rates, is much greater now than at any time in history.

Despite their recent posture of patience and gradualism, if traditional measures of inflation were to move abruptly higher, the Fed will likely react with a more hawkish tone and likely raise Fed Funds rate and resume plans to reduce their balance sheet. While the intention would be to reverse inflationary pressures, the result may be to stoke them further. Monetary velocity will become an important data point to follow to gain insight on how Fed actions might affect prices.

Given the financial market’s dependence on an accommodative Fed and low interest rates, such actions would likely reverse the asset price inflation witnessed since 2009 when the Fed began conducting such extraordinary monetary policy.

U.S. Dollar

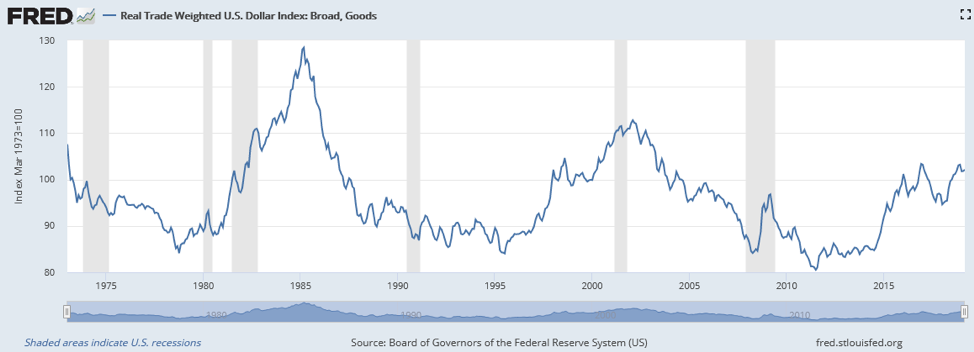

The other factor allowing the Fed to maintain such extraordinary monetary policy is the relative stability of the U.S. Dollar. Following the double-digit inflation of the 1970’s and the Fed’s drastic actions to bring it down, the dollar index rose dramatically as shown below. Upon peaking in 1985, the dollar eventually traded back to the low levels seen during the high inflation era of the late 1970s. Since that time, the dollar has been relatively stable.

As illustrated in the graph, one can spot weakness leading up to the 2008 crisis, but the dollar has since recovered. Somewhat counter-intuitively, the dollar has strengthened since 2011 despite the Fed printing money on an unprecedented scale. The reason lies in the way the value of the dollar is portrayed. The dollar index is essentially a weighted index based on cross-currency exchange rates between many of our largest trade partners. While the U.S. printed money, many other countries were following suit and the dollar was able to maintain its relativevalue.

Some of the recent strength in the dollar lies in the fact that QE has ended in the U.S. while it continues aggressively in many other developed nations. Furthermore, the Fed has been gradually raising interest rates and reducing the size of its balance sheet. These actions are currently on hold, but nonetheless, the Fed still has a more hawkish stance than most other developed nations.

A weak dollar has two major effects. U.S. exports increase as dollar-based goods are cheaper outside of the U.S., and goods imported into the U.S. from other countries become more expensive. As a net importing country, the net effect in the U.S. of the two factors above should be higher inflation. Additionally, a weak dollar bodes poorly for foreign investments in the U.S.

Over 40% of publicly traded government bonds are held by foreigners, and a sizeable share of private lending/investment is done by foreign entities as well. When the dollar declines versus the domestic currency of the foreign entity, the value of these investments declines. This, in turn, makes further investment less likely and raises the possibility that current holdings might be liquidated.

For a country that is overly reliant on debt and needs to fund current consumption and the debts of years past, a weaker dollar is a big problem. Thus, it is likely the Fed would want to prop up the dollar in the event of significant weakness. In an inflationary environment, this would be accomplished through a higher Fed Funds rate, a reduced balance sheet and Fed rhetoric, all of which would likely be troubling for risk assets.

Summary

As we mentioned, the Fed Put is dependent upon an unspoken pact and high level of trust with investors. Investors will push markets higher and take on substantial risk in exchange for the implied protection of the Federal Reserve. Today, in the wake of the Fed’s most recent policy reversal based on weak stock prices, investor trust in the Fed is seemingly greater than ever. Although there has been a great deal of turnover among Fed members, there is currently little reason to suspect the Fed will change their methods or that investors will question the Fed’s intent.

In an economy transitioning from an ultra-easy policy stance to one less so, high inflation and/or pronounced dollar weakness can happen suddenly eliciting a more severe response from the Fed. If they are unable to effectively navigate the narrow path between accommodation and inflation vigilance, the trust in the Fed that is driving markets could disappear quickly.

With so many events converging to introduce new uncertainty into the economy, the stability of markets that investors have enjoyed and faith in the Fed seems very much in jeopardy.

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.