3. And they said to one another, ‘Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.’ And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. 4. Then they said, ‘Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.’” Genesis 11:3-4 (NRSV)

Technology

Technology can be thought of as the development of new tools. New tools enhance productivity and profits, and productivity improvements afford a rising standard of living for the people of a nation.

Put to proper uses, technological advancement is a good thing; indeed, it is a necessary thing.

Like the invention of bricks and mortar as documented in the book of Genesis, the term technology has historically been applied to advancements in tangible instruments and machinery like those used in manufacturing.

Additional examples include the printing press, the cotton gin, and the internal combustion engine. These were truly remarkable technological achievements that changed the world.

Although the identity of a technology company began to emerge in the late 1930s as IBM developed tabulation equipment capable of processing large amounts of data, the modern-day distinction did not take shape until 1956 when IBM developed the first example of artificial intelligence and machine learning. At that time, a computer was programmed to play checkers and learn from its experience.

About one year later, IBM developed the FORTRAN computer programming language. Until the early 1980s, IBM was the dominant tech company in the world and largely stood as the singular representative of the burgeoning technology investment sector.

The springboard for the modern tech era came in 1980 when the U.S. Congress expanded the definition list of copyright law to include the term “computer program.” With that change, software developers and companies like IBM involved in programming computers (mostly mainframes at that time) had a legal means of preventing unauthorized copying of their software. This development led to the proliferation of software licensing.

As further described by Ben Thompson of stratechery.com –

This highlighted another critical factor that makes tech companies unique: the zero marginal cost nature of software. To be sure, this wasn’t a new concept: Silicon Valley received its name because silicon-based chips have similar characteristics; there are massive up-front costs to develop and build a working chip, but once built additional chips can be manufactured for basically nothing. It was this economic reality that gave rise to venture capital, which is about providing money ahead of a viable product for the chance at effectively infinite returns should the product and associated company be successful.

To summarize: venture capitalists fund tech companies, which are characterized by a zero marginal cost component that allows for uncapped returns on investment.

Everybody is a Tech Company

Today, every company employs some form of software to run their organization, but that does not make every company a tech company. As such, it is important to differentiate real tech companies from those that wish to pose as one. If a publicly traded company can convince the investing public that they are a legitimate tech company with scalability at zero marginal cost, it could be worth a large increase in their price-to-earnings multiple. Investors should be discerning in evaluating this claim. Getting caught with a pretender almost certainly means you will have bought high and will be forced to sell low.

Pretenders in Detail

Ride share company Uber (Tkr: UBER) went public in May 2019 at a market capitalization of over $75 billion. Their formal name is Uber Technologies, but in reality, they are a cab company with a useful app and a business producing negative income.

Arlo Technologies (Tkr: ARLO) develops high-tech home security cameras and uses a cloud-based platform to “provide software solutions.” ARLO IPO’ed at $16 per share in August 2018. After trading as high as $23 per share within a couple of weeks of the initial offering, they currently trade at less than $4. Although the Arlo app is available to anyone, use of it requires an investment in the Arlo security equipment. Unlike a pure tech company, that is not a zero marginal cost platform.

Peloton (Tkr: PTON) makes exercise bikes with an interactive computer screen affording the rider the ability to tap in to live sessions with professional exercise instructors and exercise groups from around the world. Like Arlo, the Peloton app is available to anyone, but the experience requires an investment of over $2,000 for the stationary bike. PTON went public in September 2019 at the IPO price of $29 per share. It currently trades at roughly $23.

Recent Universe

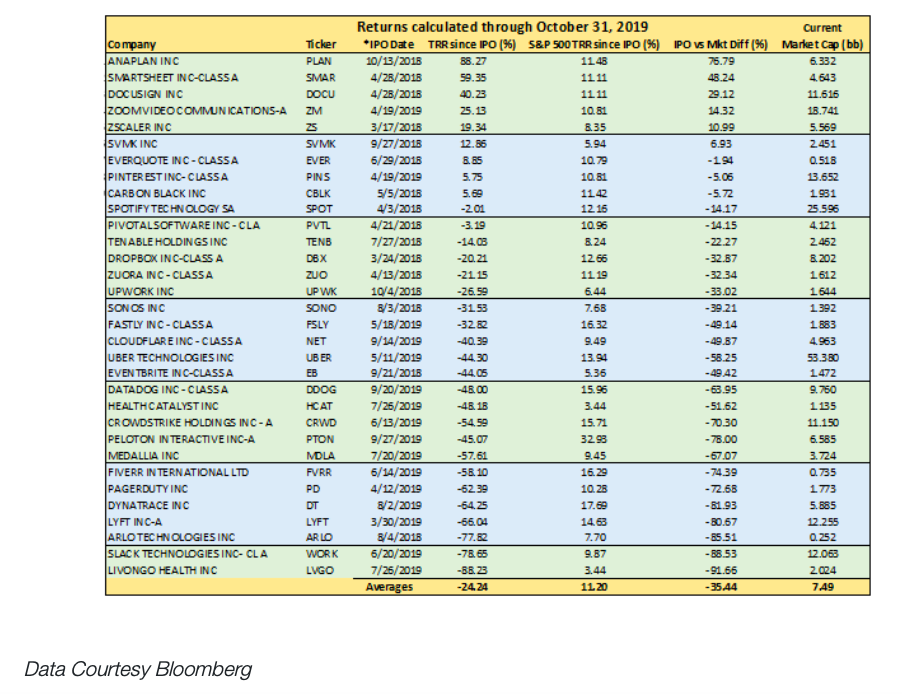

From 2010 to the end of the third quarter of 2019, there have been 1,192 initial public offerings or IPOs. Of those, 19% or 226 have been labeled technology companies. Over the past two years, many of the companies brought to the IPO market have, for reasons discussed above, desperately tried to label themselves as a tech company. Using analysis from Michael Cembalest, Chief Strategist for JP Morgan Asset Management, we considered 32 “tech” stocks that have gone public over the past two years under that guise. We decided to look at how they have performed.

In an effort to capture the reality that most investors are not able to get in on an IPO before they are priced, the assumption for return calculations is that a normal investor may buy on the day after the IPO. We acknowledge that the one-day change radically alters the total return data, but we stand by it as an accurate reflection of reality for most non-institutional investors.

As shown in the table below, 23 of the 32 IPOs we analyzed, or 72%, have produced a negative total return through October 31, 2019. Additionally, those stocks as a group underperformed the S&P 500 from the day after their IPO date through October 31, 2019 by an average of over 35%.

Summary

Over the past several years, we have seen an unprecedented move among companies to characterize themselves as technology companies. The reason is that the “tech” label carries with it a hefty premium in valuation on a presumption of a steeper growth trajectory and the zero marginal cost benefit. A standard consumer lending company may employ technology to convince investors they are actually a new-age lender on a sophisticated and proprietary technology platform. If done convincingly, this serves to garner a large price-to-earnings multiple boost thereby significantly (and artificially) increasing the value of the company.

A new automaker that can convince investors they are more of a technology company than other automobile companies’ trades at many multiples above that of the traditional yet profitable car companies. Still, the core of the business is making cars and trying to sell them to a populace that already has three in the driveway.

Using the technology label falsely is a deceptive scheme. Those who fall for the artificial marketing jargon are doomed to sacrifice hard-earned wealth as has been the case with Lyft and Fiverr among many others. For those who are not discerning, the lessons learned will ultimately be harsh as were those described in the story of the tower of Babel.

It is not in the long-term best interest of the economic system or its stewards to chase high-flying pseudo-technology stocks. Frequently they are old school companies using software like every other company. Enron and Theranos offer stark lessons. Those were total loss outcomes, yet the allure of jumping aboard a speculative circus is as irresistible as ever, especially with interest rates at near-record lows.

The investing herd continues to follow the celebrity of popular “momentum” investing, thereby they ignore the analytical rigor aimed at discovering what is reasonable and what allows one to, as Warren Buffett says, “avoid big mistakes.”

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.