One of the Federal Reserve’s congressionally charted objectives is to promote stable prices for the goods and services we all purchase. Investors have been lulled to sleep for over 20 years by “price stability.” As a result, few investors have an appreciation for how inflation can impact their investments.

Despite stable price increases for the last two decades, the Federal Reserve (Fed) now wants more inflation.

Given the negative impact inflation has on our wealth, why does the Fed wish to boost inflation? Maybe more important, how can they generate inflation?

Before progressing, we explain the hypocrisy between the Fed’s 2% inflation target and true price stability. For this, we lean on David Rosenberg quoting Alan Greenspan: “When asked at the July ’96 FOMC meeting the level of inflation that truly reflects price stability, he said, “I would say the number is zero, if inflation is properly measured.”

What is Money?

The capacity for the Federal Reserve to generate more inflation can be appreciated in a straightforward statement:

ALL MONEY IS LENT INTO EXISTENCE.

Ruminating on that statement helps you understand why inflation is not running rampant despite Fed “printing presses” running at full steam. It also provides a glimpse as to how the Fed can change that. But first, let’s consider how money is created.

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.” Those oft-quoted words by Milton Friedman define the root cause of inflation. To paraphrase, it means more money chasing fewer goods creates inflation.

Most economists agree with Friedman’s theory. The question, however, is what constitutes money? The problem facing the Fed is that they do not create money. Strike that; the Fed does not yet create money.

The Fed only provides banking reserves, or “toner,” so to speak. It is up to banks to use the reserves to make loans and create new money.

Money is Born

The following lesson of how money comes into existence is from our article, Why QE Is Not Working.

“Under the traditional fractional reserve banking system run by the U.S. and most other countries, money is “created” via loans. Here is a simple example:

- John deposits a thousand dollars into his bank

- The bank is allowed to lend 90% of their deposits (keeping 10% in “reserves”)

- Anne borrows $900 from the same bank and buys a widget from Tommy

- Tommy then deposits $900 into his checking account at the same bank

- The bank then lends to someone who needs $810 and they spend that money, etc…

After Tommy’s deposit, there is still only $1,000 of reserves in the banking system, but the two depositors believe they have a total of $1,900 in their bank accounts. The bank’s accountants would confirm that. To make the bank’s accounting balance, Anne owes the bank $900. The money supply, in this case, is $1,900 despite the amount of real money only being $1,000.

That process continually feeds off the original $1,000 deposit with more loans and more deposits. Taken to its logical conclusion, it eventually creates $9,000 in “new” money through the process from the original $1,000 deposit.”

If you notice, the multiplying, or creation, of money is solely dependent on banks. At each step in the process, a bank must decide to lend the latest deposit. With each additional loan, the money supply increases. If a bank does not lend, the money supply does not grow.

In the same way that banks create money, it can vanish. Money dies when a debt is paid off or when a default occurs.

Unproductive Debt Needs Inflation

The foundation of the modern U.S. economy is debt. That is not necessarily good or bad, but it does raise a couple of essential questions:

- Was the debt productive and used to generate future economic activity to service and repay the debt?

- Was it unproductive and used to purchase something that provides little or no income generation in the future?

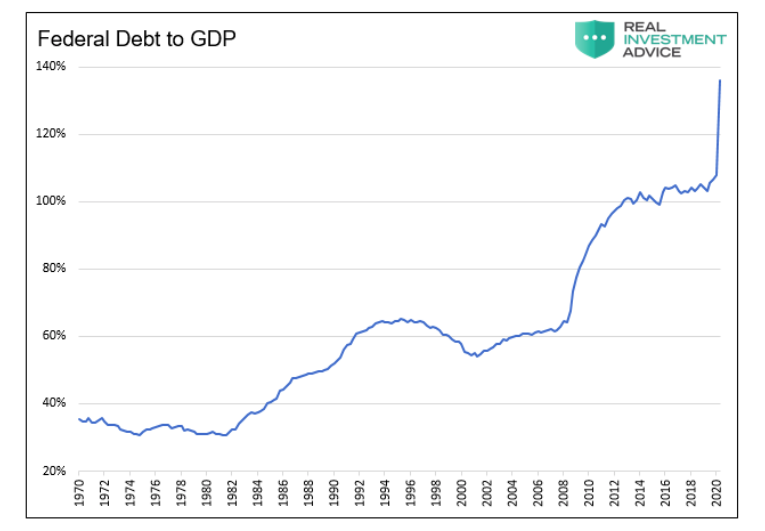

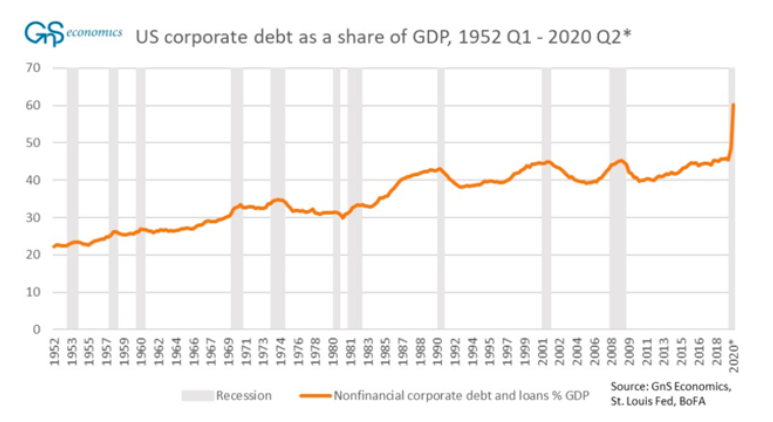

Assessing every single loan outstanding for its productivity and income generation is impossible. However, there are easy ways to qualify debt in aggregate. The graphs below show the ratio of Federal Debt to GDP and Corporate Debt to GDP.

If the debt were productive in aggregate, GDP would rise faster than debt. That is not the case nor the trend for the last 50 years. Therefore, we can say with some certainty that a majority of debt is unproductive.

It should, therefore, be no surprise that productivity growth rates inversely track the growth of the debt ratios above.

Under our economic construct, unproductive debt needs more debt at lower interest rates to sustain it. At some point, and we are likely near, or at the point, it needs inflation to reduce its burden.

More debt, especially at cheaper interest rates, allows debtors to service and pay down old debt. Inflation affords debt holders the ability to service and pay back debt with money worth less than when the loan was originated. Is it any wonder why the Fed has brought rates to zero and continually yearns for more inflation?

Back To The Fed

So with an understanding of how banks create money, and the role debt plays in the economy, we come back to the Fed.

The Fed, believing they are responsible for managing economic growth, encourages ever-increasing debt levels to keep the debt scheme going. As we said, a reduction of debt would reduce the money supply and result in deflation and further defaults. The economic fallout would be terrible.

To ensure debt balances rise, the Fed encourages new debt with low-interest rates. In 2008, zero interest rates were not enough to promote debt. During the 2008 crisis and ever since the Fed has decided to push reserves onto the banking system via quantitative easing (QE). The “logic” is that if the banks have reserves, they will gladly use them to make loans.

A Bump in the Road

Money is born when a bank makes a loan. If banks are not making loans, money is not being created. This explains why, despite the Fed’s massive efforts, inflation has yet to take hold.

Bank of America recently summed up the Fed’s problem well.

“At the current low rates, even if the Fed were to set all Treasury rates to 0bp, how many new borrowers and spenders would emerge? This is the problem of the zero lower bound that has worried the Fed and other central banks for years.”

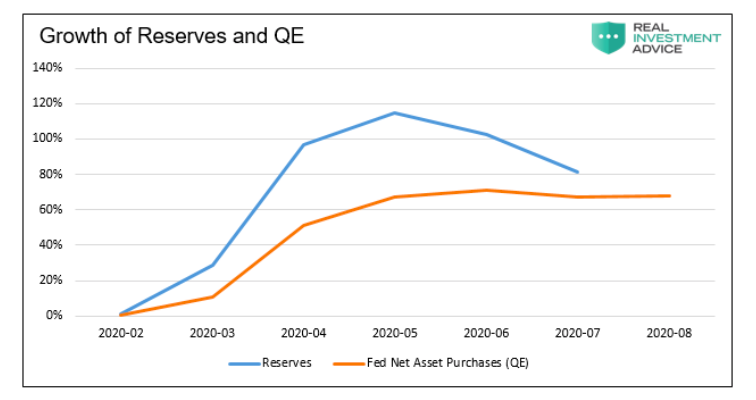

The graph below shows that since February, reserves at banks have grown faster than the amount of reserves the Fed is adding to the banking system via QE. If banks were using newly added reserves to create loans, reserve growth would be well below the growth of QE.

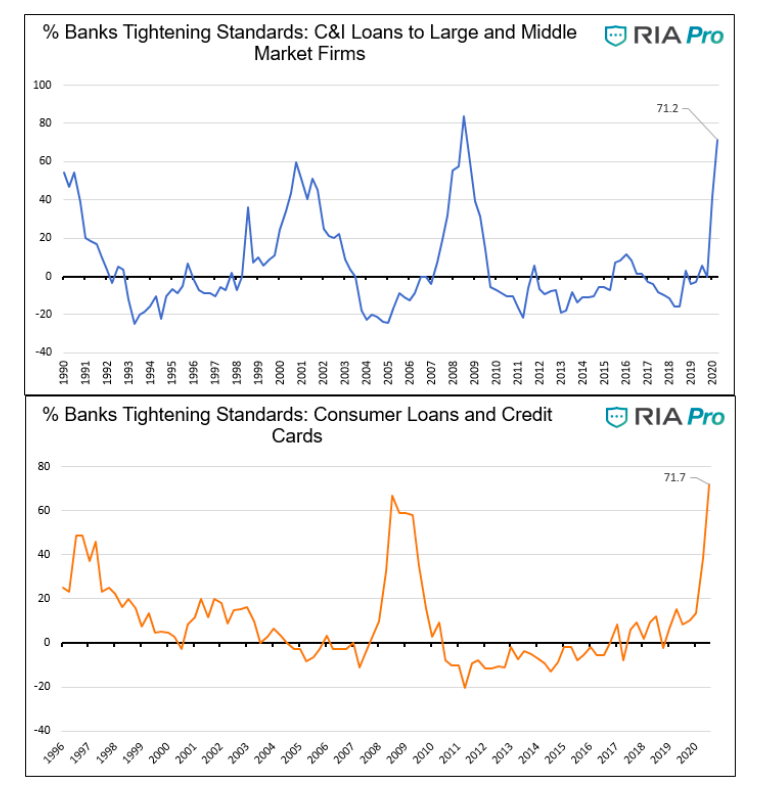

The next set of graphs shows that banks have been aggressively tightening lending standards on business and consumer loans. Also, the Mortgage Bankers Association’s (MBA) Mortgage Credit Availability Index is at a six-year low.

Worsening matters, debt is being defaulted upon due to the COVID shutdowns, and money is vanishing. Further, the savings rate is noticeably higher, and citizens are being prudent and paying off debts.

The banks have enough excess reserves to make trillions of dollars in loans. However, the banks are on the hook for defaults and solvency issues arising from such loans. Banking margins are at historically tight levels, interest rates at record lows, and the unemployment rate is up to levels rarely seen. To make matters worse, the Fed is begging for inflation, which would raise future interest rates to the detriment of bank profits. Should we expect banks to loan in such an environment? Of course not.

Bypass the Banks

“…if I was trying to create deflation like I’m in this evil Darth Vader, like ‘Let’s create deflation,’ I would have done exactly what the Fed did from 2012 until a couple of years ago.” – Stan Druckenmiller, CNBC June 2019

What can the Fed do if they cannot persuade the banks to lend, create money, and generate inflation? Ben Bernanke once told us that the Fed could print money and distribute it to the public. He referred to this as “helicopter money,” thus granting him the nickname “Helicopter Ben”.

Helicopter money may not be today’s order of business, but the Fed has hinted they may choose to become a bank and lend directly to borrowers. If the banks will not do their job, why not do it for them?

The Fed does not care about gains and losses, that’s our problem. It is a problem most citizens will not understand until they are using Benjamins in their fireplace. If the Fed loses money on a bad loan, they can print more money to offset it. Whether money is lent directly to Joe Schmo on main street, a large corporation, or the government, it would represent a new weapon in the fight for more inflation.

Think of it this way, if the Fed offered you a $100,000 “loan” at a zero percent interest rate, would you take it? No doubt many would, and as such, the supply of money and inflation would surge. Dare we say, “mission accomplished.”

Summary

If the Fed manages monetary policy with the same tools of the last decade, inflation is not likely to rise meaningfully. The Fed understands the trap its monetary policy leaves them in. To escape, the Fed may consider printing money. We suspect doing this via direct lending efforts is their way out of the trap.

A popular rebuttal to our synopsis is that it is illegal for the Fed to make direct loans. That is very true, but neither is the Fed allowed to buy corporate bonds. They chose not to abide by the Federal Reserve Act and Congress did not stop them.

As long as congressional oversight is weak and the public is blind, the Fed has the tools. If the Fed wants inflation, they can get it.

As investors, we try to anticipate what the Fed will do. Next, we try to assess the implications of those actions. This year has been one long reminder that tomorrow might not look like yesterday. Much has changed and is changing. Our decisions as investors should account for the probability that those who manage monetary policy do so for their constituents, and not being a bank, we are not their constituent.

En garde.

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.