Years of monetary policy which has consistently driven yields lower, along with economic growth, have now left investors nowhere to hide from risk.

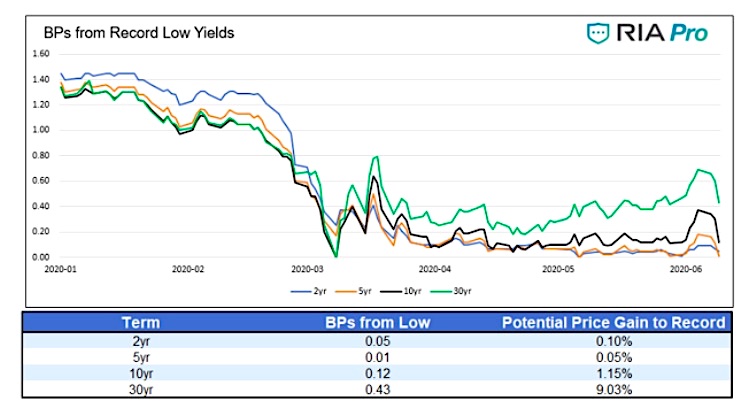

The graph above shows how many basis points benchmark U.S. Treasury securities are from their record lows.

The table at the bottom of the chart provides possible return scenarios if those bonds fall back to those records.

As you can see, the potential upside in most Treasury bonds is marginal at best.

Do portfolio managers understand the repercussions of such a return outlook? Simply, there is nowhere to hide.

Traditional Portfolio Management

Many individual and institutional portfolios have allocations to stocks and bonds. For some investors, the ratio of stocks to bonds is static. For others, it vacillates based on risk preferences and market conditions. In any case, investment advisors, pension funds, and endowments, a required allocation to bonds is both an intuitive response and a matter of legal requirement.

Ballast

Bonds play an important role in portfolio management because they provide ballast to the risk exposure of equity markets. In the prior two bear markets, diversification using bonds proved very useful. In Greater Fool Bonds we wrote the following:

“Going back to what we described above as a balanced portfolio, investors benefited greatly during bear markets from the allocation to bonds in a simple 60/40 strategy (S&P/UST). For purposes of simplicity, we assume the full 40% allocation of bonds was in 10-year U.S. Treasuries. In most cases, investors would use other high quality fixed income categories such as mortgages and investment-grade corporates as well as a range of various maturities such as 2-year, 5-year, and 10-years.

The following analysis shows how allocations to bonds helped limit downside in the last two equity bear markets.

- From September 2007 through March 2009, a simple 60/40 (S&P 500/7-10 Yr. UST) portfolio returned -23.92%. An all-stock portfolio returned -45.76%. The 40% allocation to bonds reduced losses by 21.84%.

- From January 2000 through September 2002, a simple 60/40 (S&P 500/7-10 Yr. UST) portfolio returned –16.41%. An all-stock portfolio would have returned -42.46%. The 40% allocation to bonds reduced losses by 26.05%.

Heading into the two bear markets mentioned above, the 12-month average yield on ten-year U.S. Treasury bonds was 6.66% in 2000 and 4.52% in late 2007. At their lows, the yields fell to 3.87% and 2.43% for 2002 and 2008, respectively.”

A cursory glance at current yields highlights that those benefits are no longer available.

Floored Yields

Back to our lead graph. Holding U.S. Treasuries maturing in ten years or less is likely to provide no price appreciation if yields fall to their record lows. If that’s the case, and given such low yields, those bonds are essentially cash surrogates with outsized risks.

The question for those bondholders is, why hold such bonds? Given the yields are not much above cash yields, they must believe rates can drop to new records. If they did not think that, why not just hold cash?

There are likely two factors that would lead to lower rates for the full maturity spectrum of Treasury yields.

- Deflation kicks in, boosting real yields, which entices investors to buy bonds.

- The Fed shows intent to reduce Fed Funds into negative territory.

Deflation?

Currently, inflation expectations are reduced from prior-year levels but are ticking up gradually and still well above zero. It is reasonable expectations fall if the recovery proves elusive.

Contrary, the Fed seems more than willing to push unlimited amounts of monetary stimulus until inflation is running hot. That potentially raises other problems. As the saying goes, “you can’t put a saddle on a mustang.”

Negative Rates?

Most Fed speakers, including Jerome Powell, have come out against negative rates. They seem to have noticed that such policy has damaged European and Japanese banks. The banks own the Fed, and therefore it’s reasonable to assume they will not repeat the mistakes by the other central banks.

“There’s no clear finding that it (negative rates) actually does support economic activity on net, and it introduces distortions into the financial system, which I think offset that,” Powell said. “There’re plenty of people who think negative interest rates are a good policy. But we don’t really think so at the Federal Reserve.” -Jerome Powell on 60 Minutes 5/18/2020

We certainly do not rule out negative rates but believe QE is the Fed’s preferred option.

Hedging with Bonds

While the inflation outlook and the Fed’s perspective can change, it appears yields may be at a floor. Based on the table, 30-year Treasury bonds can provide a 10% return if they decline to record low yields. Every other maturity, assuming the floor holds, will deliver cash-like returns in a best-case scenario.

Whether they know it or not, balanced portfolio managers are in quite a quandary. Will they consider Treasury notes with meager yields and little upside an equity hedge? Are they willing to hold higher duration price-sensitive bonds with limited upside as a hedge?

The benefits of hedging with bonds have certainly changed from years past. It seems unlikely that a 40% allocation of bonds can provide 20-25% downside protection, as was the case in the prior two recessions.

Other Bond Asset Classes

Investment-grade corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities may also offset equity exposure. The benefit versus Treasuries is they provide a little more yield. The cost for the higher yield are additional risks. Credit spreads on such instruments have a habit of rising at the most inopportune times.

The Fed is actively buying those sectors and not allowing risk to be priced correctly. Accordingly, those risks are minimal for now. We caution, however, the risk is higher for individual securities versus funds and ETFs representing those sectors.

Corporate and mortgage bonds offer some additional upside if their respective spreads return to their record lows. For reasons described above, that incremental benefit is limited though.

Seeking Balance

If “balanced” portfolios are no longer balanced, what is a manager to do?

For starters, they can look for alternative securities such as commodities, precious metals, preferred stocks, and convertible bonds. Those assets and a host of others are not as common or liquid but offer diversification benefits.

Second, and equally difficult for most money managers, they can hedge equities with equities. This strategy may include options, short positions, and volatility strategies.

They may also tactically position equities by reducing or adding equity exposure to manage risks.

Further, managers can actively rotate between companies and sectors to navigate their exposure.

The bottom line is the market is not providing the balance it used to, and investors will have to compensate in other ways. The sooner they figure this out, the better prepared they will be.

Summary

The new rate environment poses significant problems for passive balanced investors. Gone are the days when these portfolios self-balance during drawdowns and perform admirably in upturns.

They need to adopt new tools and change in ways to which they are not accustomed.

The traditional balance portfolio management box is broken, so investors better quickly start thinking outside of it.

The biggest concern is that most managers, so accustomed to the ease of 60-40 investing, do not recognize the emergence of this problem.

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.